Hawthorne

By Brenda Wineapple

By Brenda Wineapple

By Brenda Wineapple

By Brenda Wineapple

Category: Arts & Entertainment Biographies & Memoirs | Literary Figure Biographies & Memoirs | Essays & Literary Collections | 19th Century U.S. History

Category: Arts & Entertainment Biographies & Memoirs | Literary Figure Biographies & Memoirs | Essays & Literary Collections | 19th Century U.S. History

-

$20.00

Jun 29, 2004 | ISBN 9780812972917

-

Jan 11, 2012 | ISBN 9780307808660

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

The King and the Catholics

This Living Hand

Buchanan Dying

Konin

New York Burning

Peculiar Institution

Maya Angelou

The Wilkomirski Affair

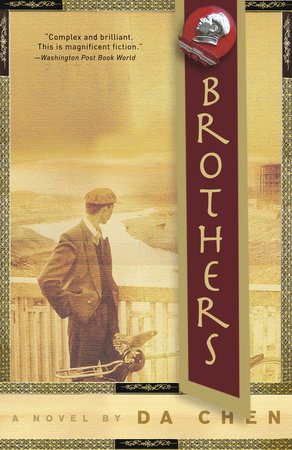

Brothers

Praise

“Clearly the best biography of Hawthorne; the Hawthorne for our time. Beautifully conceived and written, it conveys the full poignancy and complexity of Hawthorne’s life; it makes vivid the times and people and places — and what a rich array of people and events! A delight to read from start to end.”

–Sacvan Bercovitch

“Brenda Wineapple’s Hawthorne is, quite literally, an electrifying life. The power and sweep of the writing galvanizes a subject frozen, by earlier biographies, into a series of stills. We understand, finally, a man and artist torn by every conflict of his time, adding a few of his own, a man both strange and strangely familiar. The great achievement of this stunning biography lies in the feat of restoring Hawthorne to the rich and roiling America of his own period, while revealing him, for the first time, as our contemporary.”

–Benita Eisler

“With the possible exception of Herman Melville, no one has ever understood the grand tragic Shakespearian nature of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s life and work as well as Brenda Wineapple. Her brilliant, powerful, nervy, unsettling and riveting book is authoritatively researched and beautifully written; it has itself the dark mesmeric power of a Hawthorne story. Wineapple’s Hawthorne is an intensely private man, compounded of strange depths, mysterious failings, concealments, yearnings and unmistakable incandescent genius.”

–Robert D. Richardson

“Brenda Wineapple illuminates Hawthorne’s complexities without demystifying the man. He remains one of the most intriguing American writers: dark, guilty, erotic, and psychologically acute – qualities that Wineapple deftly explores.”

–Margot Peters

“There is no justice for Hawthorne without the mercy which failed him in life and art. In Wineapple’s new dispensation, all the man endured and the art achieved is revealed by loving scruple and, to awful circumstance, condolent response. No biographer since James, no critic since Lawrence has limned so unsparing and therefore so speaking a likeness of our first great fabulist, from which one returns to the works with enlightened wonder. More darkness, more light! Here both abound.”

–Richard Howard

“A fine biography…A sensitive reading of Hawthorne’s character…Wineapple makes generous use of a cache of family letters that detail the tangle and tussle of wills that Hawthorne had entered as son, brother, lover, and husband, all the while seeking the freedom of spirit to exercise his genius.”

–Justin Kaplan, Washington Post

“Meticulously researched and superbly written…captures the novelist in high resolution.”

–Peter Campion, San Francisco Chronicle

“A vivid account of a highly interesting life.”

–Brooke Allen, New York Times Book Review

“Richly detailed and nuanced; a model of literary biography and an illumination for students of Hawthorne’s work…A thoughtful and absorbing life.”

—Kirkus (starred)

“A thoroughly engrossing story of a writer’s life… written with novelistic grace and flow, with an eye to the telling detail and apt quotation.”

–Dan Cryer, New York Newsday

“Wineapple is a splendid stylist and a master of concision. She can capture an entire personality and life in a brief paragraph, … She can define a complex amatory relationship in a sentence…. Her eloquent hands bring Hawthorne vividly alive for us.”

–Jamie Spencer, St. Louis-Post Dispatch

21 Books You’ve Been Meaning to Read

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

Find Out More Join Now Sign In